|

Italian Literature in WW1

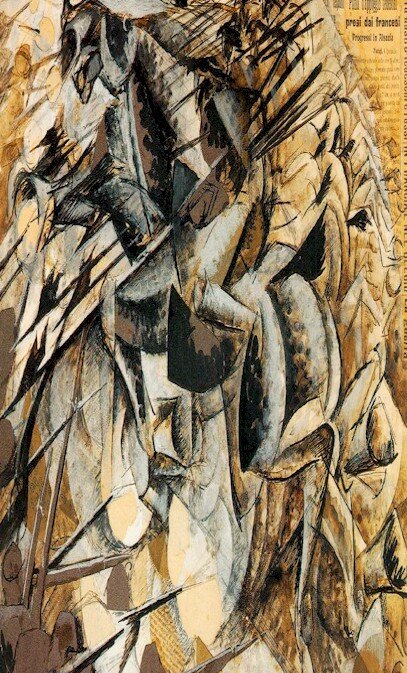

In 1909, Italy saw the birth of “Futurism” [E1] [E2] [I1] [I2] [F1]

[S1]

[S2]

a revolutionary movement, which spread in both art and poetry.

It was actually inspired by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who expounded his new ideas in his famous “Manifesto”, published in French in Paris in 1909 [F1]. Like other artists such as Boccioni [I1] [I2] [E1] Carrà [I1] [I2], he rejected late romanticism and academic tradition, and advocated a new kind of poetry, dynamic and aggressive, glorifying war and celebrating courage and rebellion. The Futurists loved speed, noise, machines, pollution, and cities; they embraced the exciting new world that was then upon them rather than hypocritically enjoying the modern world’s comforts while loudly denouncing the forces that made them possible. Fearing and attacking technology has become almost second nature to many people today; the Futurist manifestos showed an alternative philosophy. It was also to be based on precise canons such as the free association of words, the elimination of grammar and syntactic links, the use of verbs in the infinitive, etc. Futurism, however, did not have the same impact on literature as it had on visual arts.

Manifesto of Futurism [E1]

- We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

- Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

- Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggresive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

- We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath - a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

- We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

- The poet must spend himself with ardor, splendor, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

- Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

- We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!... Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

- We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

- We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

- We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.

The end of World War I and the advent of Fascism [E1] [I1] [S1] meant a return to conformism, although some poets went on writing in original and quite personal ways. Between the 1020s and 1930s a new poetic tendency appeared, called Hermeticism [I1] [I2], including such names such as Eugenio Montale, Salvatore Quasimodo and Giuseppe Ungaretti, who wrote quite difficult poems in an elusive, abstruse and “hermetic” style which privileged evocation and verbal suggestion rather than direct communication. After them we can also remember Dino Campana who wrote in a very original and visionary style, and Mario Luzi who, in his pre-war output, was one of the most important voices of Hermeticism. Two poets separate from the hermetics were Umberto Saba who wrote memorable poems about his family and his native city of Triste, and Vincenzo Cardarelli who expressed his inner world through the descriptions of seasons and landscape.

11/18

11/18

|