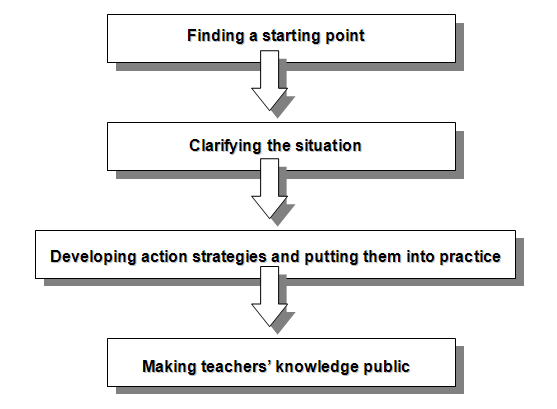

Many authors (including Lewin [E1]) have designed

graphical models to represent the process [E1] [I1] [S1] of Action

Research. Almost all these models present a cyclical structure and involve

problem identification, data collection, data analysis, and action steps as

recurring stages in consecutive cycles of Action Research. It might be helpful

to those who are approaching Action Research for the first time to underline

the fact that there is no need to take those models literally, as they are

generally conceived as an outline of a process formed by different stages. For

example, no time period is applied to an action research cycle as a rule: it

might last either three months or two days, depending on the aim.

Only when the models are

merely considered as graphical tools to help conceptualise the action research

process can they prove useful. One of the clearest and most understandable

model is given by Altrichter, Posch and Somekh. According to them, some typical

broad stages can be found in any Action Research process:

The first stage of a research process

involves finding out and outlining a feasible starting point. That is,

individuating a very specific question regarding the classroom practice that

needs urgent or prompt attention. This might be a practical problem (e.g. a

class that is particularly disruptive) or a feeling, something that makes the

teacher uneasy while performing a certain task in a classroom (e.g. assessing

students’ oral presentations).

The best way to think of a starting

point for action research is to conceive it as the first impression.

Once the impression has been perceived and fixed, the teacher-researcher can go

on investigating in order to go beyond the impression and reach a deeper

understanding of the practical theories by which his/her actions are led.

One of the most helpful and useful tools

since the beginning of the process outlined above is the diary. As well

as representing a more familiar procedure compared to other research methods,

diaries can contain data collected in other ways such as unstructured classroom

observations or the context and conditions of an interview that has been

performed. Moreover, the researcher can easily insert in a diary his/her own

ideas and insights that may be useful in developing theoretical constructs that

will, in turn, prove essential when interpreting the data collected.

There is (it goes without saying), a

number of methods for collecting data; it will be up to the researcher to find

out the most suitable for the situation he/she intends to analyse. For

instance, a tape recorder may be the best way to collect data regarding oral

presentations and verbal interactions in general, while a camera would be the

best device to store data involving non-verbal codes and messages (such as the

teacher’s gestures and the students’ unsaid reactions, for example).

One of the distinguishing features of

Action Research is its collaborative dimension: being able to rely on other

people’s help as observers is fundamental for the teacher who engages in an

Action Research process.

If a group of people is available and

willing to cooperate, they can carry out what is defined as ‘analytic discourse

[E1] in a group’. This

involves analysing a given issue (or problem) by asking questions to the

teacher who proposed the issue. It is very important not to be judgemental and

avoid reporting similar experiences at this stage. The aim of questioning the

researcher is to help him/her focus on even the smallest and apparently

insignificant detail of a given situation. Analytic discourse usually leads to

a satisfactory in-depth understanding of a problem for the teacher reporting in

particular and for the whole group on a general level.

When finding a group of co-workers turns

out to be impossible, something close to analytic discourse can be carried out

by means of a critical friend. This may be a fellow teacher or, even

better if we are dealing for the first time with action research, an external

expert. A critical friend should ask open or exemplifying questions in order to

help the teacher report on a particular situation, but should never provide

suggestions or be critical at this stage.

After having collected data and

developed theories, an Action Research cycle calls for action. This means

developing and, above all, putting into practice action strategies in

order to bring about changes into everyday practice. Trying out new action

strategies can be compared to field experimenting. As Schön puts it, “Since

teaching is characterised by complexity, ambiguity and development, it is not

possible to plan what will happen in a classroom with any certainty. As this is

the case, teachers become researchers when they investigate their practice to

evaluate its appropriateness in terms of their educational aims”.

It is fundamental, while classroom

practice is being modified, to monitor the process carefully in order to draw

proper conclusions, share them with fellow teachers and go on starting a brand

new cycle of Action Research.

To sum up (quoting Altrichter, Posch and

Somekh), Action Research makes an important contribution to:

the professional development of individual

teachers who improve their practical theories and competence in action through

reflection and action;

the professional development of individual

teachers who improve their practical theories and competence in action through

reflection and action;

curriculum development and improvements in

the practical situation under research by developing the quality of teaching

and learning through new and successful action strategies;

curriculum development and improvements in

the practical situation under research by developing the quality of teaching

and learning through new and successful action strategies;

the collective development of the

profession by means of opening up individual practice to scrutiny and

discussion and thus broadening the knowledge base of the profession;

the collective development of the

profession by means of opening up individual practice to scrutiny and

discussion and thus broadening the knowledge base of the profession;

the advancement of educational research.

the advancement of educational research.